ChatGPT, AI and the Publishing Industry

While I had various things planned for this update, I decided to write instead about the elephant in the room: ChatGPT, recent advancements in large language models (LLMs) and consequences (already realized and potentially upcoming) for the publishing industry.

(I do include a short project update at the end for those who are following along.)

ChatGPT and Recent Developments in AI Language Models

The world that I write into today is in many ways a different world than the one I wrote to a year ago. Since it’s been such a whirlwind, even for those of us who have been watching closely, I think it’s worthwhile to sit down and actually list out the changes:

ChatGPT1 (and the related Bing interface) brought LLMs into the public awareness in a big way. This is worth noting because GPTs are not themselves new and were already growing more powerful over time. OpenAI’s GPT-3, which predated the release of ChatGPT, was an impressive model in its own right2. But while ChatGPT was originally based on a souped-up version of GPT-3, the key difference was putting the chat interface over the top of it. For the first time, the general public could interact with it directly, making the technology much more concrete to a lay audience than the more abstract developments that had gone on before.

GPT-3.5 (which ChatGPT was originally based on) was quickly superseded by GPT-43, a model even more impressive than its predecessor. The short time between announcements coupled with the impressive step up in capabilities has led to dramatic speculation about the future of AI.

Despite being “just” a text-completion engine, LLMs like GPT-4 can solve an impressive array of problems, including reasoning and arithmetic4, answering questions5, and data cleaning and analysis6. While the accuracy in each of these areas is never perfect, and for information retrieval queries in particular the models often provide made up and incorrect answers7, these abilities far exceed what anyone reasonably expected LLMs to be able to do prior to the release of ChatGPT.

Needless to say, there are a lot of reasons to be excited. At the same time, we have plenty of reasons to be concerned, even aside from the sometimes wild speculation about future capabilities:

As noted above, ChatGPT (even after recent improvements) provides incorrect answers if used as a direct query interface. In one particularly notable case, a lawyer relied on ChatGPT to generate legal filings for a client without checking the generated references. ChatGPT not only made up cases, but also their contents. The judge was not amused8.

This is made worse by the fact that we tend to anthropomorphize LLMs, a trend encouraged by ChatGPT’s use of the first-person pronoun “I” in reference to itself9. Lay users are understandably confused about the actual capabilities of such models.

Chat interfaces for LLMs are vulnerable to prompt injection attacks, in which the protections applied to these models are circumvented by the end user10. Though I haven’t watched this space too closely, as far as I know every version of ChatGPT has been found to be vulnerable. This means that LLM tools cannot be configured for safety—for whatever definition of safety we might choose. It is best to assume that LLMs will be used for nefarious purposes, whether that be to improve the efficacy of spam and phishing or something worse.

In the publishing industry, the availability of LLM tools such as ChatGPT has led to a flood of content, overwhelming some publishers with submissions11. Submissions—already one of the acute pain points of aspiring authors, as discussed in last year’s newsletter—are likely to get even worse, making the process of getting published that much more difficult.

LLMs benefit from being trained on a large body of existing work12. But the vast majority of these works are protected by copyright—a legal framework intended to give authors control over the works they publish and financial compensation for their use. While some claim that AI training qualifies as “fair use,” and therefore need not require consent or payment to authors, this is far from settled legally. I am aware of at least one active lawsuit on this topic13.

Users of ChatGPT send the contents of their queries to OpenAI, the company that builds ChatGPT. By default, these prompts can be used by OpenAI to improve their software, which means that sensitive personal or corporate information may be used to train future versions of ChatGPT or other LLMs. This is problematic, especially considering the poor boundaries users exhibit in their usage of the tool.

What AI Means for the Publishing Industry

When it comes to predictions about the future of AI, it can be difficult to separate realistic possibilities from more speculative ones. (And some of the speculation is pretty wild14.) But it seems clear that AI—as a tool, and not necessarily as a general intelligence—is already here, and will likely improve in the near future. Even in that limited context, AI will undoubtedly have an impact on the publishing industry.

The first and most obvious question is whether AI tools (whether ChatGPT or some successor) will be used to write books. I think the answer to this is clearly yes, but it comes with some major caveats. First, as noted above, various aspects of the legality of AI have not yet been settled, making this a risky proposition for anyone who takes their writing career seriously. Even if using ChatGPT made writing a book, say, faster by a factor of two, that wouldn’t be worth it if it make you subject to copyright lawsuits, or put your own copyright at risk. (Not to mention the fact that publishers might refuse to publish it, even aside from the outcomes of any legal questions.)

But even then, it’s clear from the initial stories coming out about ChatGPT that even with the ability to generate coherent text, these tools do not remove the need for a keen editorial eye. Both at the micro level—ensuring that the word-by-word flow of the text meets your stylistic goals—and the macro—designing the overall arcs of the story—hard work is required to ensure a quality product. This is no gold rush, no matter what the people selling shovels claim.

Is it possible that AI tools will get to the point where they can generate entire novels from scratch with no or limited human intervention? Sure, it’s possible. But we’re now back in speculative territory. What I can say based the capabilities we have today is that AI-based tools will likely be an important part of the publishing industry moving forward, but that it would take another breakthrough (or multiple breakthroughs) before we’d see them fully replace humans.

On the other hand, generating text is only one narrow use case for AI. There are far more places in the publishing process where AI could be used, and where it could deliver results. For example:

What if agents began using AI to filter submissions? Queries might not get read by a human at all if they can’t pass the AI’s quality bar.

What if publishers replaced editors with AI? Your first-pass editorial letter could be written by ChatGPT instead of by a human.

(Repeat this for proofreaders, copy editors, beta readers, etc.)

What if publishers used AI tools to generate cover art for books automatically? Would authors have a choice if their art wasn’t done by a human?

These are just a few possibilities. And they may be less distant than they initially appear. Human workers on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform are reportedly using AI tools to automate their jobs. And this is on a platform whose sole and explicit purpose is access to human labor. What happens when publishing companies, knowingly or unknowingly, make use of AI tools to automate parts of the publishing process? I suspect that within the next decade this will become commonplace in the smaller publishers, who often need every efficiency they can get just to survive; and the larger publishers probably won’t be immune either. As an author, it will be even more important to understand what you’re getting from these services, and what risks they expose you to.

As Benedict Evans points out, the automation of work doesn’t mean that humans will necessarily lose jobs. But the efficiency gains could mean that your editor’s attention is split between that many more books (because they can edit them more efficiently). Or conversely, as costs come down, it could become much more affordable to create graphic novels and other resource-intensive media. We could be on the verge of a revolution in partially or fully animated audiobooks—think the audiobook equivalent of music videos. Who knows? I’m spitballing here, but it certainly seems plausible.

This last line of thinking is the one I like best. It’s tempting to think of AI as primarily making our existing work easier (and therefore, possibly making some portion of our human workforce obsolete, whether in creative industries or elsewhere). But it’s far more transformative to think about what this might enable us to do that’s not possible right now.

My Experience with Generative AI

Disclaimer: As is my usual practice, I waited a couple months before posting this to the web. In that time, OpenAI announced DALL-E 3, which promises to address many of the issues I had below. (Granted, these images were generated with MidJourney. But presumably competitors will follow.) The field moves quickly, but I think it’s still worth documenting my experiences at this point in time.

As mentioned above, language models frankly aren’t worth the risk for authors right now—and therefore, I’ve been steering clear.

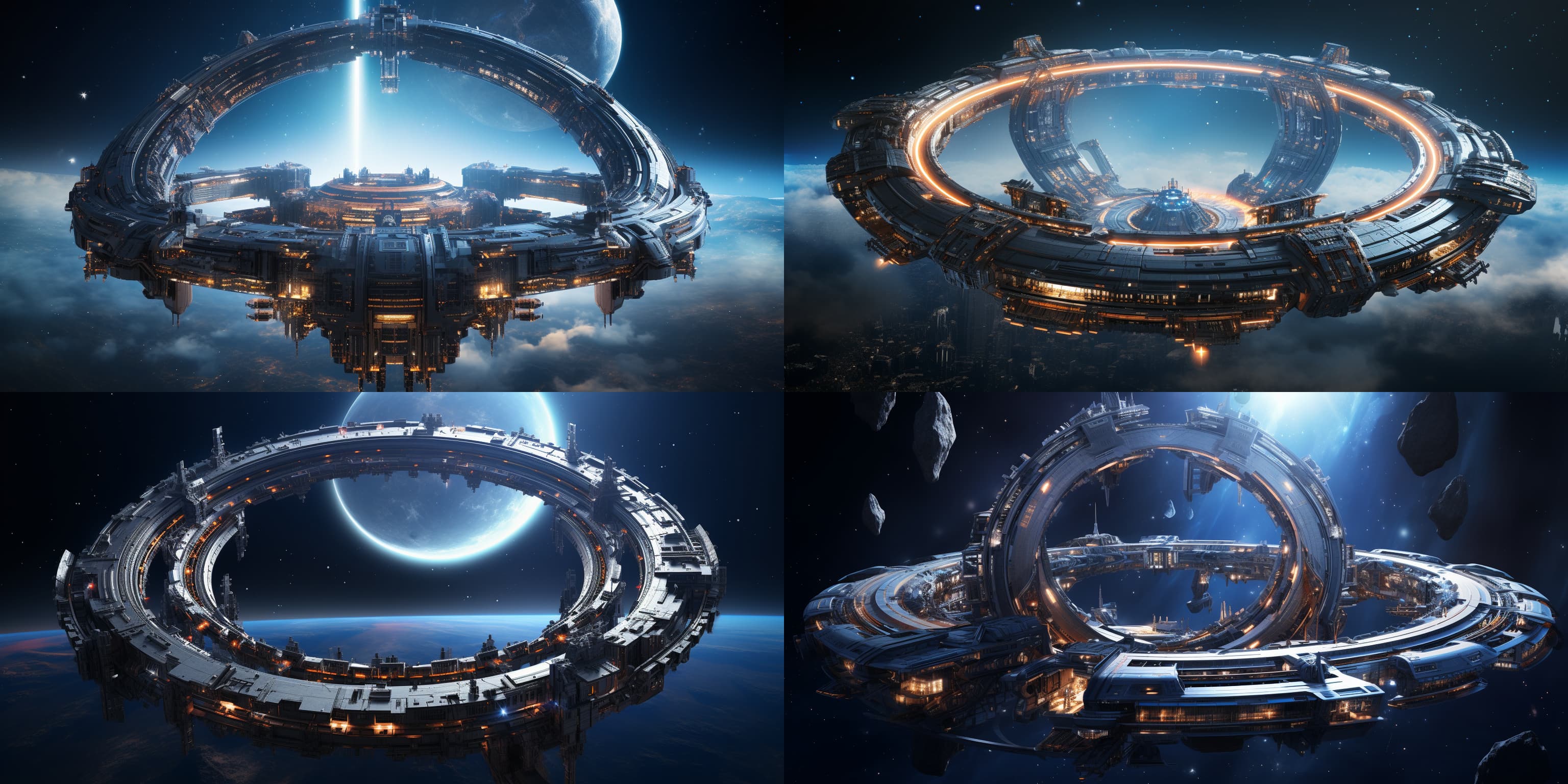

But I have used generative AI models for images: DALL-E 2 and MidJourney 5. These are models that take a text-based prompt and generate an image output as a result. So I wanted to talk a bit about my experience trying to use these tools for generating sci-fi related art. Here’s an example I generated recently (using MidJourney):

That’s pretty good for a first attempt! I should say, before you get too excited, that this is not a concept that will ever appear in any of my books. (Again, copyright is one of the major outstanding issues with AI, so I intentionally try to stay away from my own concepts while generating these.)

I am not an artist. I am not ever going to be an artist. The fact that I can just put this into a prompt and get an image out is fantastic.

But of course it’s not all roses.

I added “shaped like a half circle” to the prompt, assuming the model would basically take something like my previous image and cut it in half. Nope. All of the results still contain full circles, and some now even have multiple circles. The two images on the left have two planets instead of one, and the lower right seems to have no planets at all.

Let me try again and remove “spaceframe,” in case that’s confusing it.

Now the model seems to have figured out I wanted something crossing the circle through the middle, but it didn’t remove the second half of the circle.

All of these images are pretty. If I’d created art like this, I’d be very proud of it. This is a property of MidJourney, which tends to generate “artsy” looking images in general. But the challenge—if I were to use this in a book—would be not so much getting good-looking pictures, but getting ones to match the image in my head. Even seemingly direct instructions get ignored or confused.

I’ve tried using MidJourney to generate alien concepts, and the situation there is even more hopeless than it is with battleships. It’s not impossible, if you’re willing to let yourself be guided by what the model is able to generate, rather than what you want the aliens to look like. But the model seems to lean strongly into the green martian vision of aliens, and it’s somewhat challenging to get it out of that rut.

One of the other challenges with generating art is that you can’t really use the same character or object twice. For example, let’s take that original battleship concept and try to put it on top of a desert planet instead.

What I did in this case was use an image prompt, with the image of the original battleship as the first part of the prompt. Then I modified the text to specify a “desert planet”.

We can clearly see two issues. First, only 1 out of the 4 generated images looks remotely like a desert planet. But more importantly, the battleship changed! None of the outputs looks close enough to the original to pass for the same ship. This could be another ship in the same fleet, but there’s no way to pass it off as the same ship (unless heavily modified).

This means that serial art—where you show the same character(s), over and over—is basically impossible with generative AI right now. I can generate images that follow a pattern, but I can’t place very tight constraints on what I actually get out.

Overall, the results are both astonishing and kind of underwhelming. They’re astonishing, in the sense that if you’d told me 10 or even 2 years ago that we’d be able to generate art like this on the fly, I wouldn’t have believed you. On the other hand, once you start really digging in, the limitations become obvious really quickly, and the process of getting what you want can be quite tedious (if not impossible).

Obviously, ChatGPT is a different beast entirely. But I suspect that many of the same limitations will apply. For this reason, despite the dramatic advances, I still think it’s not entirely obvious whether we’re on the verge of a dramatic revolution in AI capabilities, or if the path we’re on will bring us to an ultimately underwhelming future.

What do you think? Are we on the verge of a revolution or a new AI winter? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

The Exander Project in 2023

After my last update, I decided to pause sending queries for my first book. It’s not that I ran out of agents to query. Even with as many queries as I sent, there are more out there who I didn’t get to query yet. But querying is just too distracting. I found that I couldn’t concentrate on anything else while I was doing that, and ultimately it was holding back progress on the other stuff I wanted to be doing.

As a result, I was able to finally sit down and start writing again. That wasn’t my initial plan after my last update, but I think it’s gone well. Writing again has been a blast, and frankly a relief coming from the query trenches.

I was hoping to be able to write in this update that I completed the new book, but I’m not quite there yet. As a result, I won’t say too much more about it for now. Of course, if you want to know more, I’m always happy to answer questions.

After the book is done, then I’ll be back to the same cycle as last time: edits, beta readers, critiques, queries, etc. As always, if you want to help out, feel free to let me know.

Get Future Updates Faster

I send updates to the mailing list (often months) before posting them publicly on the website. If you want to get these updates earlier, sign up for the mailing list below.

I manage the list personally and use it only for project updates; it will never be shared with third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time.

OpenAI announced ChatGPT on their blog on November 2022. But it wasn’t until Microsoft made it widely available through Bing search in February 2023 that it really took off in the public consciousness.↩︎

GPT-3 was described in an OpenAI white paper in 2020, with public availability later that year. Techniques for alignment to human instructions were released in 2022.↩︎

GPT-4 was announced via an OpenAI research article in March 2023.↩︎

OpenAI provides instructions for the GPT-3 model on how to improve accuracy for reasoning and arithmetic tasks. Reading through the page should give you a good sense of what the model is capable of. (It also comes with helpful citations to research articles for further discussion.) Notably, asking the model to “think step-by-step” improved accuracy from 18% to 79% according to one paper that studied GPT-3. Note that these results are for GPT-3, and one would generally expect GPT-4 to perform better on average.↩︎

Donald Knuth posed a set of 20 questions to be answered by ChatGPT and posted the questions and answers online. (Also discussed on Hacker News.) Knuth expresses his astonishment at the answers, though several of the answers have obvious flaws. Another HN user took the same questions and posed them to an upgraded version of ChatGPT based on GPT-4, and the answers were even more impressive (from Hacker News).↩︎

Terrence Tao reported using GPT-4 for solving an issue with processing data scraped from web pages and PDFs for a conference he was responsible for.↩︎

The makers of OpenCage, “an API to convert coordinates to and from places,” reported that users were signing up for their service based on recommendations from ChatGPT. The problem? They do not actually offer the service that ChatGPT tells users they offer, nor is it a service they can (or would want to) offer. This type of made up response is called a “hallucination” in the literature, though some commenters have argued that actually, ChatGPT is doing its job, which is not to provide accurate answers (it is not a database) but to provide text completions that match a pattern.↩︎

Multiple Hacker News threads have followed the case as it has made its way through the court.↩︎

For a critique of the language used by LLMs and suggestions for improvement, see “Talking About Large Language Models” by Murray Shanahan (discussed on Hacker News).↩︎

As best I can tell, the outputs of ChatGPT are steered by OpenAI in two main ways. First, ChatGPT is “fine-tuned” in a form of training that takes a general-purpose LLM (in this case, GPT-3.5-turbo or GPT-4) and “aligns” its output what is expected for chat sessions. TIME Magazine famously reported that OpenAI paid $2 per hour to Kenyan workers to train ChatGPT. However, this training is at best imperfect and does not necessarily avoid undesirable output. In addition, OpenAI further tunes the output of the model by providing a “system prompt” that is placed ahead of the user prompt. It is this prompt that can be circumvented via prompt injection to enable restrictions on ChatGPT to be removed. Of course, these safeguards do not apply to open-source models at all, so even if OpenAI were to address these issues, unrestricted AI models would still exist.↩︎

Clarkesworld, a respected science fiction magazine that publishes short stories, was forced to close submissions due to dramatic growth in the number of submitted stories, the vast majority spam generated by AI tools. They later reopened, though the AI submissions have not stopped and fighting them continues to be an ongoing battle. I suspect that the magazine was especially vulnerable because the short story format is well within the capabilities of AI (at least in terms of quantity, not necessarily quality), but I’m guessing it may not take long for this to become a common trend throughout the industry.↩︎

Though OpenAI has not told us exactly what data they used to train ChatGPT, it is safe to assume it included large swaths of content on the internet, and possibly also books.↩︎

One high-profile lawsuit concerns the use of a related product, GitHub Copilot. Copilot is like a ChatGPT for code. And it is trained on (among other things) the body of open source software available on GitHub. Ironically, while this software is freely available, it it still protected by copyright. And the lawsuit aims to show that Microsoft (owners of GitHub and significant investors in OpenAI) have used this open source software improperly, in multiple senses. Case updates are being tracked on the lawsuit website.↩︎

As an example of this sort of speculation from an AI researcher, see excerpts from an interview with Douglas Hofstadter, who appears to be in grief as his sense of human uniqueness is crumbling. I wouldn’t go that far, particularly before we see where LLMs and other AI models actually land. But certainly, one can easily imagine futures in which we will have to grapple with these questions.↩︎

The Exander Project

The Exander Project